Jensen huang is a man literally schooled in adversity. When the co-founder of Nvidia, America’s most valuable semiconductor company, was first sent to boarding school in Kentucky, little did his Taiwanese relatives realise that it was a school for troubled youths. He shared a room with a knife-scarred boy fresh out of prison. On some days he would either be picked upon or forced to clean the toilets. Far from buckling under the strain, he has said he learned to tolerate discomfort. That is a useful skill in the highly cyclical world of silicon chips.

Listen to this story. Enjoy more audio and podcasts on iOS or Android.

Your browser does not support the element.

Save time by listening to our audio articles as you multitask

Once again, the industry is in meltdown. In the tail end of the covid-src9 pandemic in late 202src, when almost no one—from car companies to cryptocurrency miners—could get their hands on chips, semiconductor manufacturers, or fabs, went on a spending spree. Capital spending soared by almost 75% in six months compared with pre-pandemic levels, says Malcolm Penn of Future Horizons, a forecaster. Because of long lead times, much of that new capacity is still under construction. Yet in the meantime inflation, economic slowdown, Chinese lockdowns and a cryptocurrency collapse have buffeted demand. The purchase of computers and smartphones has also slowed. The result is a chip glut as stark as shortages were a year ago, hitting many chipmakers’ profits.

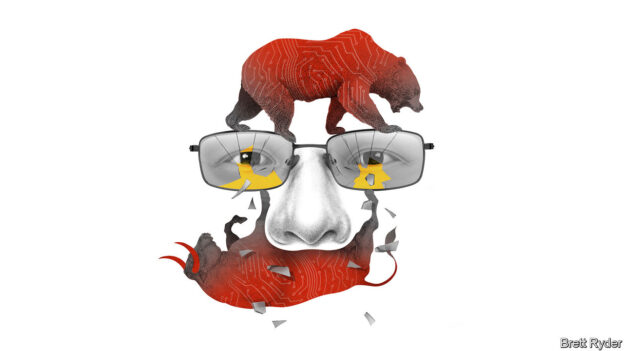

That even includes Nvidia, which has replaced Intel as the bluest chip of American chip companies. On August 24th it reported a staggering slide in second-quarter earnings, while slashing revenue forecasts for the third time since May. From a peak valuation of more than $800bn in late 202src, it is now worth less than $400bn. True to form, Mr Huang remained sanguine. By early next year, he said after the earnings release, he expects exciting new chip architectures for data centres and gaming, Nvidia’s two biggest businesses, to revive its fortunes. Yet as he looks through his spectacles at the dazzling new models that he thinks will change the face of artificial intelligence (ai), as well as more nebulous concepts like the metaverse, is there a danger that he is underestimating the brutality of the here and now?

For short-term investors, there obviously is. Things could get worse, especially in crypto. Nvidia has long been sniffy about the way cryptocurrency miners have bought up its graphics processing units (gpus), chiefly designed for gaming, to mine Ethereum’s ether, the second-largest cryptocurrency. The last time its revenues crumbled in late 20src9, the main culprit was a collapse in the price of ether, which it had woefully underestimated as a risk. That crash was short-lived. By the time the pandemic hit a few months later, the craze for ether helped propel Nvidia’s stratospheric stockmarket recovery. Matt Bryson of Wedbush Securities, a broker, says that at the peak sales of chips for crypto mining may have generated about 20-25% of its gaming revenues. However reluctant Nvidia was to associate with the cryptoverse, the serendipity played hugely in its favour.

No longer. This year the price of ether has tanked, and though Nvidia acknowledges the problem, it makes no attempt to quantify the impact. Moreover, Ethereum is thought to be on the verge of switching its blockchain technology used to validate transactions from “proof of work”, which uses massive number-crunching powered by Nvidia’s gpus, to a less energy-intensive mechanism called “proof of stake”, which will make gpus redundant. Partly in anticipation of this, crypto miners have dumped their gpus onto second-hand e-commerce sites like eBay, contributing to a sharp fall in prices. With revenues from Ethereum gone for good, the fear is that the crypto winter could turn into an ice age.

Another source of concern for investors stems from the use of gpus in what Nvidia calls data centres and which includes cloud computing and the processing of ai. A negligible business six years ago now eclipses gaming, once Nvidia’s main source of revenues. Supply-chain disruptions meant that data-centre growth fell short of the firm’s expectations in the second quarter. Moreover, though gpu demand from America’s cloud providers such as Amazon, Microsoft and Google increased from the first to the second quarter, this was more than offset by weak sales to their counterparts in China. On August 3srcst Nvidia conveyed more bad news when it warned it could suffer a $400m sales hit from new rules by the American government requiring it to obtain a licence before shipping some of its most advanced ai chips to China. There are other worries, too. One of the biggest is that, as the drive to accelerate the speed of ai models gathers pace, America’s cloud providers will rely on their own chips, rather than Nvidia’s gpus. Competition from smaller chip designers could also heat up.

To the metaverse and beyond And yet Mr Huang can probably afford to remain insouciant. That is because, however cyclical the industry, several factors are likely to strengthen Nvidia’s leading position in gpus over the longer term, expanding its “moat”. First, it is still reaping the rewards of a decision to supply software, known as cuda, as well as chips, so that programmers can fine-tune the latter to their own specifications. Even if the cloud providers make their own chips, the software makes it easier for their enterprise customers to stick with Nvidia’s gpus. Second, Nvidia is betting on a brand new data-centre chip cycle that could hugely increase ai-processing capacity in areas ranging from writing texts to understanding life sciences. These “foundation models” are surging. Third, it leads in supplying chips for autonomous vehicles that, after many false starts, Mr Huang says could be Nvidia’s next billion-dollar business.

It may be common for tech bosses to shrug off short-term busts to keep the focus on long-term dreamscapes. But the good thing about chip busts is that however nasty and brutish they are, they can also be mercifully short. It’s a fair bet that when this one turns, Nvidia will still be at the forefront of the industry—and that semiconductors will be more crucial than ever. ■

Read more from Schumpeter, our columnist on global business:

Could the demonised oil industry become a force for decarbonisation? (Aug 25th)

For business, water scarcity is where climate change hits home (Aug src7th)

Tencent is a success story bedevilled by the splinternet (Aug src3th)

For more expert analysis of the biggest stories in economics, business and markets, sign up to Money Talks, our weekly newsletter.

This article appeared in the Business section of the print edition under the headline “Seeing through the chip cycle”

From the September 3rd 2022 editionDiscover stories from this section and more in the list of contents

Explore the edition

Read More

Comments are closed