There was a time when nobody cared what offices looked like on the inside. In the 1960s, America’s architects were mostly preoccupied with erecting iconic buildings along city skylines. Few concerned themselves with ergonomic chairs, acoustics, office layouts, biophilic design, or other corporate amenities that we obsess about today.

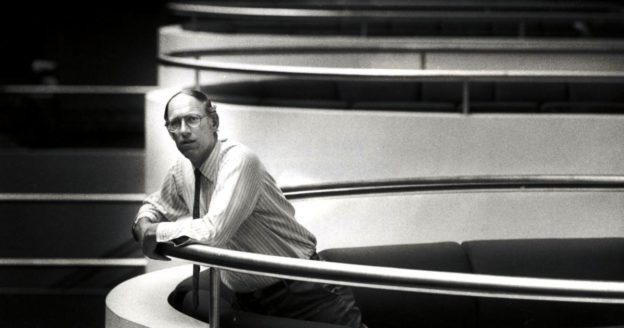

The contemporary focus on office interiors is thanks to Art Gensler. The Brooklyn-born architect, who passed away on May 10 at age 85, first gained renown as an interior architect when he opened his practice in 1965. Starting with two towers in San Francisco, he proved how designing attractive interiors could attract tenants to newly-constructed buildings. The focus on a building’s interiors, which he called “inside-out design,” eventually helped his eponymous firm become the world’s largest architecture practice. Today, Gensler has over 6,000 employees in 50 offices, working on projects in more than 100 countries.

For an architect to focus on interior design was “unbelievably innovative” in those days, explains Andy Cohen, co-CEO of Gensler. Corporate interior design even had a rather wonky name: tenant development. “It meant that you were designing designs for the tenants or the people, not the building. At that time, no one focused on the occupants,” he explains. “A lot of the office spaces tended to look the same—walls, ceiling, and carpet.”

Gensler was dogged about designing for comfort and productivity. For a time, he was obsessed with office chairs. Melissa Mizell, a design principal at Gensler’s firm, described Gensler’s extensive process to find the perfect seating for every project in a 2014 San Francisco Chronicle profile by John King.

“He had me call suppliers to pull every single chair known to man, so the client could try them out…We had at least 50 here in the office. Art cared about the chair,” Mizell told the Chronicle.

“That’s the level of detail he got because he cared so much about people,” Cohen tells Quartz. “His perspective was always about looking at things through other people’s eyes and putting himself in their shoes. It’s always about the user experience.”

But before “user experience” or “empathy” became industry buzzwords, even Gensler’s first employees were confounded by the idea of pouring their energies into building out spaces inside towers built by other firms.

“My employees would constantly say to me: Art, when are we going to do real architecture?,” Gensler said in a 2014 interview with the University of California, Berkeley. “But I think architecture is design—and design is inside and out. Most people were designing from the outside in—what is it going to look like [externally] and we’ll figure out the stuff that will go in it. That never made sense to me.”

Over time, Gensler’s persistence in prioritizing interior spaces that respond to shifting work styles would prove key to the firm’s success. The firm’s co-CEO Diane Hoskins, who started the Gensler Research Institute, says their mission became widely understood after Peter Drucker’s 1993 book Post-Capitalist Society. The so-called “father of modern management” argued that companies should shift their attention from manufacturing and other business processes, to their people. These knowledge workers needed the right environment to thrive.

“In many ways, our firm really became the vanguard at the beginning of this era,” she explains.

Hoskins says Gensler’s offices have become laboratories for the latest ideas in workplace design. When she joined the firm in 1995, recalls that they had redesigned the firm’s Washington, DC, office to evoke the ethos of the start-up boom. They had exposed pipes on the ceilings, raw concrete, and an actual garage door for the main conference room. “It’s because so many entrepreneurial startups started in garages and great ideas started [in?] a garage,” explains Hoskins. “And you know, I think he loved that we had really pushed the envelope.”

Cohen, who has been with the firm for 40 years, says his longtime boss and mentor had been thinking about next evolution of the office after the pandemic. In one of their last conversations, Cohen recalls Gensler describing how residential interior design might improve offer solutions for the office.

“He said, why don’t we take that idea and apply it to the open plan, where we have more living room settings and den settings and a sense of choice for where people can work,” recalls Cohen. “Art definitely kept saying, ‘Let’s design it so that people have a choice when they come back to the office.’”

Beyond the physical look of corporate spaces around the world, Gensler also redesigned how big architecture firms are run. Eschewing the lone genius model of many practices, he appointed Cohen, Hoskins, and his son David as co-CEOs when he stepped down from the role in 2005. (David resigned in 2015.) “It’s that collaborative spirit that proliferates our whole firm,” says Cohen. “It comes back to this idea that it’s not about one ego, one star.“

Comments are closed